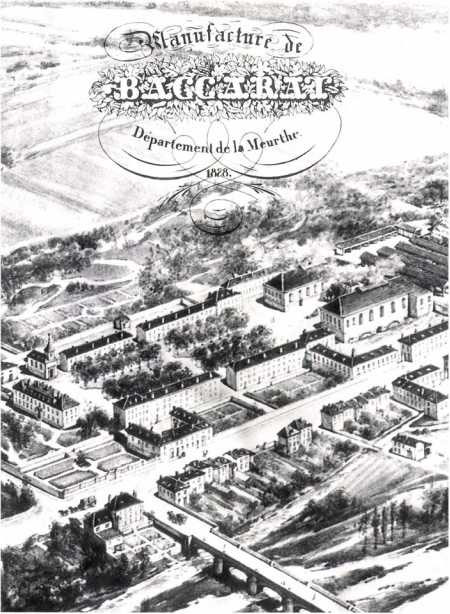

3.1 Antique Baccarat washroom weight

CHAPTER THREE

Classic Period

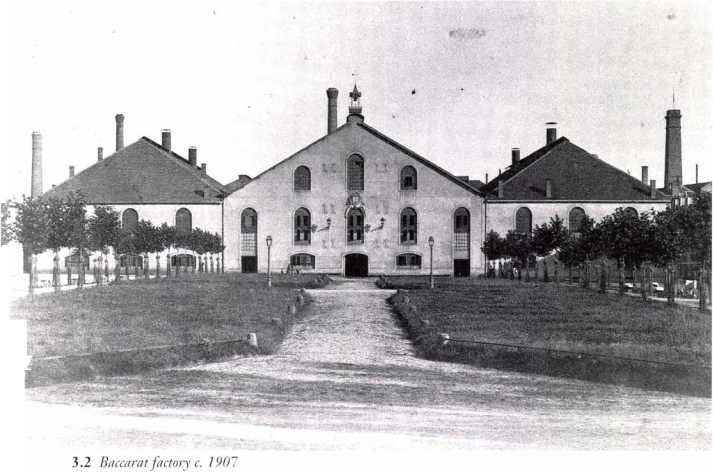

3.3 Aerial view of Cristalleries de Baccarat. I 828, from a painting

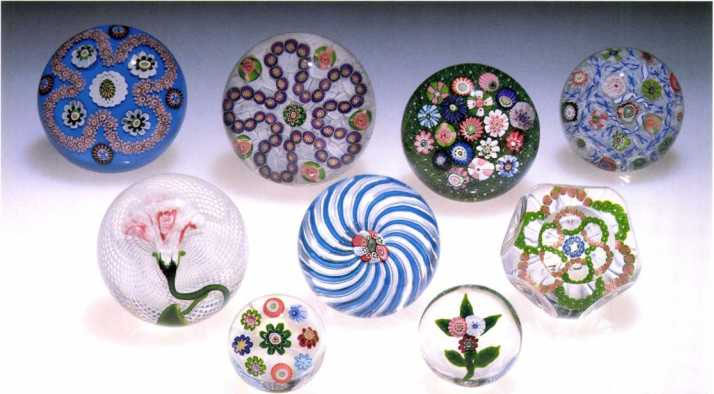

the French Revolution in 1789, the factory employed over four hundred workers and that seventy families were housed on the factory’ grounds.

As happened in many eighteenth-century factories, conditions at Verrerie de Sainte Anne deteriorated dramatically from 1790 to the time of the fall of Napoleon in 1815. Because of the war, the British blockade, the rising price of materials, and the shrinking labor force, the company suffered

great financial hardships. In 1811 the company shut down two furnaces and kept onlv seventy of its four hundred workers.

In 1816, the factory was sold to M. Aime- Gabriel d’Artigues for 2,845 ounces ol pure gold. D’Artigues had worked as director of the Saint Louis factory and had operated his own glassworks in Voneche, near Liege, until that region was abruptly declared Dutch (later Belgian) territory

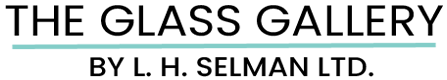

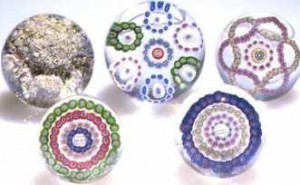

3.4 Antique Baccarat weights

company in 1823 to three of his associates, M. Pierre-Antoine Godard-Desmarets, M. Lecuyer, and M. Lolot, who formed the Compagnie des Cristalleries de Baccarat. In 1844 it assumed the name Compagnie des Verreries et Cristalleries de Baccarat and in 1881 its current title: Compagnie des Cristalleries de Baccarat.

Godard, the major stockholder of the company, believed that the future success of Baccarat depended on the perfection of its glassware and the training of its craftsmen. He insisted on using the finest materials and on improving and expanding the company’s line of production. At that time Baccarat, which was producing stemware, perfume bottles, candelabra, and chandeliers, exhibited frequently in Paris.

In 1846, under the management of Emile Godard, Pierre-Antoine Godard’s son, the craftsmen at Baccarat perfected the production of millefiori paperweights, which were then added to the company’s line of glasswares. By 1848 lampwork flower and bouquet patterns were also being produced. Paperweight manufacture at Baccarat was a small but significant part of the company’s production line for almost twenty years. During the late 1860s, paperweight production declined, but Baccarat records show that paperweight making continued at the factory on a very small scale until just after W orld War I. Some believe Baccarat weights were made up until 1934. Often the name Dupont is associated with weights made between the years 1931 and 1934 [3.5]. It was not until the 1950s that the art of making paperweights was actively rex’ ived at Baccarat.

3.5 So-culled “Dupont” weights

manufacturing techniques. In 1772 the Academic judged that Saint Louis’s lead glass was equal in quality to the highly regarded English flint glass.

During its first vears Saint Louis changed directors many times, but this did not hinder the growth and success of the factors’. In 1782, under the direction of Gount tie Beaufort, Saint Louis was the first glass factory in France to perfect the manufacture of crystal. Bv 1786 Saint Louis employed seventy-six workers in its flourishing crvstal department.

In an effort to protect the valuable trade infor-

Saint Louis

On February 17, 1767, three years after the establishment of Verrerie de Sainte Anne (Baccarat), King Louis XV gave permission to M. Rene-Fran- yois Jollv and Company to build a glass factors using the name Verrerie Royale de Saint-Louis in the Munzthal forest of the Lorraine region in the former county of Bitche [3.6]. It ss as an ideal location because of the abundance of wood, sand, and potash. For centuries this area had been a center for the production of “broad” glass (sheet glass for windows and mirrors made from bloxvn cy linders xvhich xvere opened out and flattened).

In the early eighteenth century, France was trailing other European countries in the production of fine glass. In 1760 the Academic- Royale des Sciences offered a prize to the factory’ that could make the best suggestions for improving glass

mation that was being discovered and utilized in the glass industry, the French State Council decreed in 1785 that a two-year notice must be given in order to resign from the Saint Louis staff and that permission must be obtained for traveling more than one league from the factory. The transmittal of technological information concerning glass production was a crime punishable by death. This attitude, however, did not prevent Aime- Gabriel d’Artigues, manager of Saint Louis from 1791 to 1795, from establishing a glass factor)’ at Voneche in 1802, and later, from owningand managing Verrerie de Saint Anne (Baccarat) from 1819 to 1822.

With the introduction ol pressed glass in 1820

and with Saint Louis’s increased specialization in fine glassware and crystal, the company adopted a new name in 1829: Compagnie des Cristalleries de Saint Louis. Two years later, Saint Louis and Baccarat decided to sell their glassware through a retail operation and entered into a joint agreement with the firm of Launay, 1 Iautin et Cie. in Paris.

Because of its ranking just behind Baccarat, Saint Louis tried to attract customers by developing new lines of articles. Thus it is not surprising that it was the first French factory to show an interest in the production of paperweights. One of its first millefiori weights was dated 1845, and by 1848 Saint Louis was producing a wide range of lampwork pieces as well.

- Launay, from the Paris retail firm, was enthusiastic and opinionated about the paperweights and wrote to the director of Saint Louis encourag- ing, advising, anil sometimes criticizing the factory’s efforts:

The fruit anil flower weights you have sent us are awful. You cannot imagine the bad impression made by such merchandise, the surest way of stopping the selling of them is to go on sending us weights of that quality; the shape is poor, the filigree badly set, [it] does not form the basket, the fruit is made anyhow; were they made by someone different from the workman usually in charge of them?

As paperweights became more popular and as other companies began producing them, Launay urged Saint Louis to branch out and produce other articles as well. The factory began to utilize its paperweight-making principles for all sorts of objects such as inkstands, penholders, wafer dishes, water glasses, and other pieces that could incorporate millefiori decoration. Launay also attempted to influence style and quality:

Amongst those we have received from you we have chosen one which is a fine composition and which will sell well. I bis type is generally well made; but it is still necessary to look for a way to improve it so as to create as much lightness as possible in the composition of the bouquet. If we are returning it to

you it is so that you may notice how the white enamel flower detaches itself from the other colors. Return it to us as soon as you can and those which we will want from you will generally have the white flower.

Saint Louis exhibited in many of the Paris exhibitions, but like Baccarat decided not to attend the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, thus allowing Clichy to take top honors. The last recorded exhibit of Saint Louis weights was at the Paris Exposition in 1867. Interest in the objects was on the decline and a creative and rich era of paperweight making at Saint Louis was drawing to a close.

Clichy

Because of the unfortunate destruction of company records, very little is known about Clichv-la- Garenne (in some places referred to as M. Maes, Clichy-la-Garenne), the third of the great French glass factories. Established by Messrs. Rouver and Maes, even the founding date and original location are uncertain. Two possibilities are 1837 at Billan- court, or 1838 at Sevres. It is known that shortly after the business formed, the operation was moved to Clichy, which is now a suburb of Paris.

At first the factory produced inexpensive glass for export, but by the 1840s both Saint Louis and Baccarat were concerned by the company’s rapid

3.8 . hitit/lie Saint Louis weights

3.9 Antique Clichy weights

growth and the improving quality’ of its glassware. As early as 1844, Clichy exhibited with Baccarat and Saint Louis in Paris, where the young company’s exquisite colored and overlay crystal was highly praised.

It seems that paperweights were part of Clichy’s overall plan to entice customers away from the

more established factories. M. Launay wrote to Saint Louis in 1849:

’ I ‘he selling ol weights has now gone mostly to Clichy, which cannot fulfill all the orders received. This article [paperweights] has given a great importance to this factory by the contacts that were established through it with buyers who were not in the habit of applying there. Two furnaces are now permanently burning; a third one shall probably be lit up soon.

In 1849, Clichy created quite a stir with the development of a new type of glass that the company introduced at the Champs Elysees Exhibition in Paris. The new glass was much lighter than the traditional lead glass yet retained the desirable optical properties of conventional crystal. It came to he termed “boracic” glass, because boric acid was used as a flux in its manufacture. The jury at the exhibit praised the new glass and said it rivaled lead crystal. Recent studies at The Corning Museum, however, indicate that Clichy used lead glass for paperweights.

Over the next decade, Clichy continued to en- jov a period of growth and success and in 1851, as the only French glass factory to show in the (Jreat Exhibition in London, received international acclaim. It has been suggested that Clichy glass- workers were hired by English firms to set up similar production lines because its glass was so highly regarded.

Clichy participated in the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in 1853, displaying paperweights, perfume • bottles, door knobs, and other fine crystal objects. The paperweights at this exhibit greatly influenced the production of American weights.

After 1870 the quality of Clichy s glassware and paperweights declined drastically. A few years later the company was sold to an established glassworks in Sevres and stopped making paperweights.

Pantin

L’ntil Albert Christian Revi published his article “The ‘Fourth’ French Paperweight Factor}” in the 1965 PCA Bulletin, little was known about the Pantin glassworks. Fortunately, through Revi’s extensive research a skeletal history’ of the glass factory and its products has emerged.

In 1850, E. S. Monot established a glassworks at La Yillette, near Paris, under the name of Monot et Cie. After moving the company and opening a showroom in Paris, the glass factory moved again to Pantin, No. 84, rue de Paris. By 1873, Monot had been joined by his son and by M. F. Stumpf. The title of the firm was changed at that time to Monot, pere et fils, et Stumpf.

The Pantin glassworks produced glass tubes and chemical glassware, as well as fine crystal table glasses, tumblers, perfume bottles, and chandeliers. Pantin’s wares were said to compare with those of Clichy.In 1878, Monot, pere et fils, et Stumpf exhibited paperweights as well as other glassware in the Lhiiversal Exposition in Paris. The United States sent a delegation to the Exposition to stud}– the industrial products being shown by other countries. Of particular interest is the following excerpt from the report of L .S. delegate Charles Colne on the Pantin display:

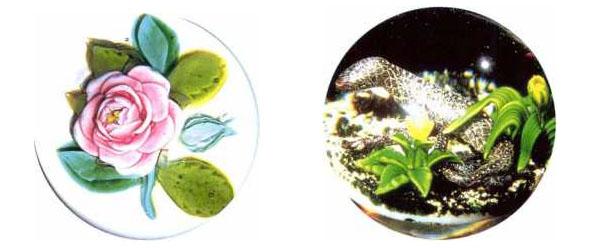

Paperweights of solid glass, containing glass snakes, lizards, squirrels, and flowers; air-bubbles are distributed in the mass, looking like pearl drops… Paperweights in millefiori of roses, leaves, and fruit, embedded in clear glass … A reptile paperweight, containing a lizard of colored glass, which had been cut in several parts before being inclosed in the glass … a coiled snake with head erect, of two colored glasses, cut in spots to show both colors, mounted upon a piece of mirror; an interesting piece of workmanship, showing great dexterity in coiling the snake.

3.13 Antique Pantin salamander weight

One of the major sources of frustration concerning the identification and attribution of Pantin weights is that no known weights by the factory were signed or dated. To add to the problem, the French factories during the classic period were reluctant to allow their wares to be pictured in reports or articles for fear of revealing trade secrets toother manufacturers. From Colne’s description, however, Revi was able to speculate that several weights formerly unidentified or tentatively attributed to other factories were most probably made by Pantin.

In 1981, Dwight P. Lanmon contributed even more information to the Pantin mystery in his article “A Pantin Discovery,” also published in the PCABulletin. While he andT. 11. Clarke, Sotheby’s London connoisseur, were searching for paperweights to be included in Coming’s 1978 Great Paperweight Show, Clarke discovered an important reference in the archives of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. Pantin had given the Conservatoire a gift in 1880 that included “a paperweight, flowers and salamander.” Although the museum was unable to locate the paperweight, Lanmon was able to study one of the other gifts given by Pantin, a “serpent metalise, ecailles brillantes”(metalized serpent, brillant [cut] scales). Because of the special lampwork techniques used, this piece provided Lanmon with valuable information that has since allowed him to identify several Pantin lizard weights.