Collecting

IN’ HIS ENTERTAINING AND INFORMATIVE BOOK,

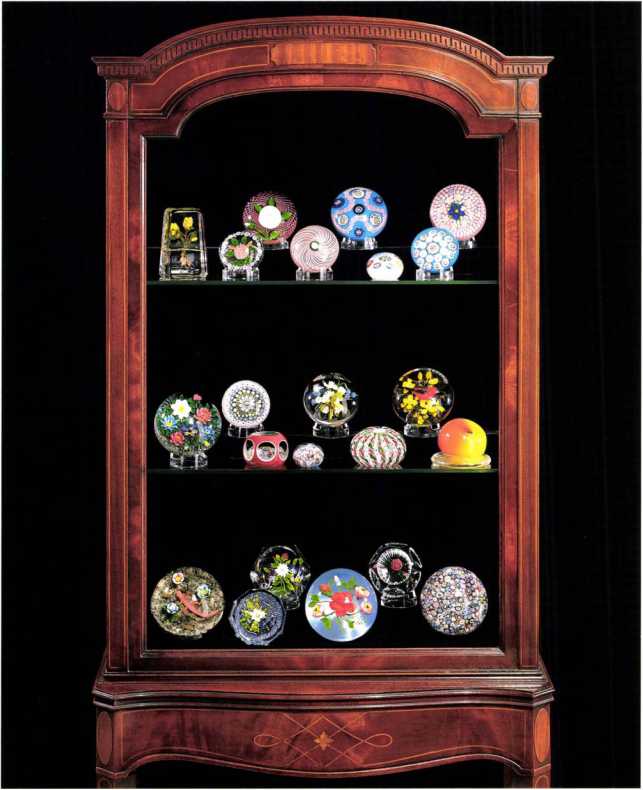

A Garland of Weights, Frank Manheim suggests that it he left to poets yet unborn to describe masterpieces which even color photography cannot adequately portray. But because paperweights cannot be captured on the page, they are even more eagerly sought in the hand. Paperweight collections ranging from those displayed in embassies and palaces to those stuffed in cupboards and bureau drawers reflect the range of collections possible. Indeed, as his book details, there are as many different kinds of collections as there are collectors.

Charles Woolsey Lyon, considered by some to be the dean of American paperweight dealers, wrote many years ago:

Collecting finer paperweights is not just a hobby or a thrilling interlude in the monotony of everyday life; I chose rather to consider it a recognition of past masters in the arts known only to those now extinct fancy glass workmen of the mid-nineteenth century … to the fancy glass makers we owe more than we realize. To us they have given the privilege of viewing, in compact form, the art of glass making in its highest degree of perfection.

The relatively obscure practice of collecting paperweights began as soon as there were weights to collect, and has never ceased to attract people.

The well-known writer Colette decorated her apartment in the Palais Rovale with paperweights, many of which she found in Paris flea markets. King Farouk, Queen Mary, Eva Peron, Truman Capote, Robert Guggenheim, and scores of other famous and infamous personalities have been serious collectors.

Early paperweight collectors had very little information available to them about their favorite objects. Prior to the publication of Evangeline Bergstrom’s Old Glass Paperweights in 1940, only a few obscure pieces had been written on the subject. Following Bergstrom’s landmark book several other important works were published, including Roger Imbert and Yolande Antic’s l.es Presse-Papiers Franqais de Crista/, E. M. Elville’s Paperweights and Other Glass Cariosities, and T. H. Clarke’s 1952 “Notes on a Terminology for French Paperweights.”

Interest in paperweights increased steadily in the United States after World War II. Collector Paul Jokelson began publishing material on the subject and encouraging contemporary glass factories and artists to make paperweights. Then scholars, especially Paul I lollister, began research and publication in this field. The popularity of paperweights grew dramatically. When collections amassed in the twenties and thirties began to

appear at auction houses and sell at high prices, the investment potential of these unique objects made them seem even more desirable to collectors.

As one example of the rise in value of a single paperweight, consider the fascinating history of the Pantin silkworm weight. It was first bought by Mrs. Applewhaite-Abbott in the late 1920s for£26 (S59). Her collection was sold at auction by Sotheby’s in 1953, with this weight selling for £ 1200. It was purchased at auction for King Farouk by another dealer. However, the day of the auction King Farouk abdicated his throne and the dealer was left with the piece. Then it was sold again. Eventually Paul Jokelson purchased it. When the Jokelson Collection was sold at Sotheby’s in 1983, this weight was bought by Arthur Rubloff for the record-breaking price of $143,000. Rubloff gave his entire collection including the prized Pantin weight to the Chicago Art Institute, where it is now on permanent display.

6.3 Punt in silkworm weight

Developing a Collection

Developing a Collection

There are many different approaches to collecting paperweights. Collections can be built on selected antique pieces; contemporary annual editions from Baccarat, Saint Louis, or Perthshire; or innovative weights by American studio artists. Collectors may choose to concentrate on a particular maker or a certain type of weight, such as lampwork flowers or sulphides. No matter what approach is taken, the key to developing a good collection is knowledge and attention to quality. Paperweight collectors distinguish themselves by taste rather than the size of their collection or income; their carefully selected collections emphasize quality rather than quantity’.

Because of the breadth of the field and the multitude of somewhat obscure details necessary in determining originality and authenticity’, collecting or investing in paperweights is a challenge. This challenge is well met, however, with expert advice and prudent buying. As in all fields of collecting, the need to rely on outside expertise decreases as knowledge grows. It is hoped that this book will give the reader ready access to a considerable body of know ledge; serve as a reliable guide through initial encounters; and, with time, become a trusted and well-worn companion to a collection of excellence.