CHAPTER FIVE

Contemporary Makers

Thf.rk wkrk a kkw ISOI VI Kl) l\S IWCI’SOI paperweight production during the 1920s and 1930s in both Europe and America. But it was not until after the Second World War that the paperweight renaissance truly began. The growing interest in antique weights, the rising value of such pieces in the marketplace, and the limited quantities available helped set the stage for the revival of paperweight making as an art form in the 1950s.

One of the driving forces behind production of contemporary paperweights was Paul Jokelson, an importer and avid paperweight enthusiast. During the early 1950s, Jokelson approached two of the famous glass factories of the classic period—Baccarat and Saint Louis—and urged them to revive the art of paperweight making.

Paperweights had not been produced in significant numbers for more than eight}’ years, and glass artisans at the two factories were faced with the task of rediscovering the almost lost techniques. Once they succeeded, the grow ing interest in contemporary weights led to further experimentation and production.

.As soon as modern paperweights became commercially successful, more glass factories joined Baccarat and Saint Louis in producing them. Cris- tal d’Albret, Perthshire, Whitefriars, and others

began utilizing traditional techniques and classical motifs as well as exploring new possibilities in design and technology.

This chapter is divided into three sections: Furnace Work Lampwork Cold Work

which correlate to the three main ways in which paperweights are made. The major technical difference in these three situations is the origin of the glass. Factories use furnaces or large vats to make their own glass, a pontil rod is used to collect the gather, and the molten glass is formed and shaped. A factor}’ has the ability to produce more weights of one particular kind, and a factorv usually, although not always, utilizes a team approach to paperweight production. Most studio artists use lampworking techniques to work with solid glass slugs that are purchased commercially. These slugs are melted down and manipulated into shape over a small gas burner or torch. In cold work, cold glass is manipulated through mechanical means, especially cutting, sandblasting, and polishing.

New areas emerge as these factories and artists reach the edges of creativity and then expand beyond them. Still the essentials remain unchanged: the artist, the glass, and the fire. Objects of beauty and mystery emerge from their skilled hands.

Furnace Work

In this section we begin with the major factories, followed by the individual artists who use this technique.

Baccarat

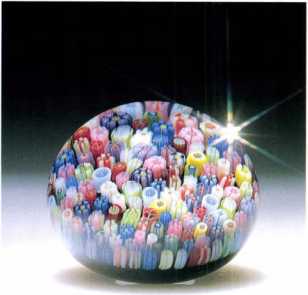

In October 1951, a magnificent millefiori paperweight was found in the cornerstone of the old parish church at Baccarat, which had been severely damaged during World War II. The weight, which included an 1853 date cane, contained 233 millefiori canes. The piece was made by Baccarat’s master craftsman at that time, Martin Kayser. The dis-

5.2 Antique Baccarat close packed tuillefiori (1848)

covery of the “Church Weight,” as it has come to be called, helped rekindle interest in paperweight making at Baccarat.

The first contemporary weight made by the factory was not, interestingly enough, a millefiori design. Because Baccarat had no records of the millefiori technique, it took several years of research and experimentation before its craftsmen finally succeeded in producing some millefiori pieces in 1957. By that time the company had already rediscovered, mastered, and begun production of anotherstyle of paperweight—the sulphide.

Baccarat began making sulphide paperweights in 1953, again at the urging of collector and connoisseur Paul Jokelson. The first attempt, which was a piece based on Dwight D. Eisenhower’s

5.3 Baccarat Eisenhower sulphide

campaign medal, was unsuccessful. But the experiment proved to the craftsmen that encasing cameos in glass could be done.

Later that year the factory produced its first successful contemporary sulphide to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. This paperweight, which portrayed the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh in double profile, was extremely popular and led Baccarat to the production of a long series of sulphides.

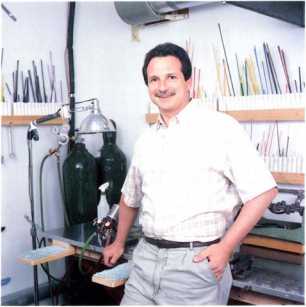

In 1968, Baccarat craftsman Jean Benoit began working on lampwork-style paperweights. With the advice and help of American paperweight maker Francis Whittemore, Benoit soon mastered the technique, and in the early 1970s Baccarat added lampwork weights to its contemporary line. In 1974 Baccarat began producing a lampwork collection for each year, using one theme throughout. These weights present a variety of flowers, fruit, or animals on clear and colored grounds [5.8].

- 5.5 Outside the Baccarat factory

All Baccarat contemporary weights hear an acid- etched seal that includes the words “Baccarat, France” and the outlined forms of a goblet, decanter, and tumbler. An interior date/signature cane and the number of the item are often included in special limited edition weights. Most Baccarat sulphide weights are inscribed on the edge of the bust with one or more of the following pieces of information: the artist’s name, the year the sculpture was created, and the name of the subject [5.7].

- 5.6 Baccarat acid-etched seat

5.8 Baccarat Oriental Collection

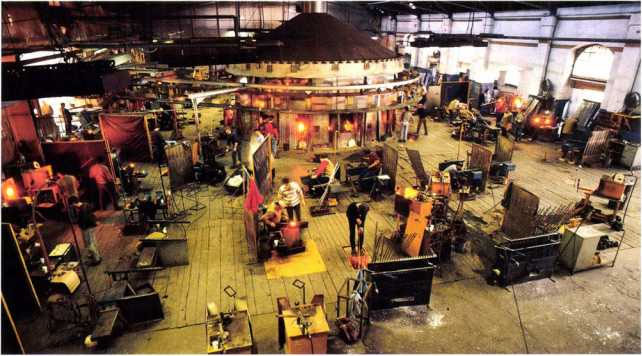

5.10 Inside the Baccarat factory

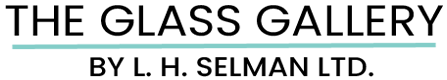

Baccarat Millefiori: By 1957 Baccarat had mastered the millefiori technique and was producing a few fine millefiori paperweights. These pieces, which were marked #1 to #9, or dated 1957, were not distributed commercially. In 1958 the factory produced its first weights for sale; these weights contained the figure 8 for theyear of identification. Later that year weights with canes bearing the tw elve signs of the zodiac in black and white opaline were introduced. These zodiac canes are included in modern Baccarat close packed millefiori to help collectors distinguish them from antique pieces.

To commemorate Baccarat’s bicentennial the factory created a limited edition of special millefiori weights that included a cane inscribed “Baccarat 1764-1964.” Twenty-six of these pieces were marked from A to Z, twenty filigree weights were marked from #1 to #20, and twenty couronne weights were marked from #21 to #40. These paperweights were primarily given to Baccarat employees and were not made available to the public.

Over the years Baccarat designs have grow n to include a wide variety of patterned millefiori motifs, carpet grounds, filigrees or “semis dc perlcs,” and mushroom overlays. Baccarat millefiori weights generally contain from 180 to 220 canes.

In 1971 Baccarat revived the Gridel silhouette canes. These marvelous silhouettes based on the cut-outs of a child had been considered a trademark of the factory’s millefiori work during the nineteenth century (see the story’ of the Ciridel canes in Chapter Four). A series of eighteen weights was produced over a period of eight years. Each of these contemporary Gridel weights has an enlarged central animal cane surrounded by a millefiori pattern including the other seventeen Gridel canes. The rooster and the squirrel, which were the first pieces produced in the series, w’ere issued in quantities of 1200. Each subsequent design was limited to not more than 350 pieces.

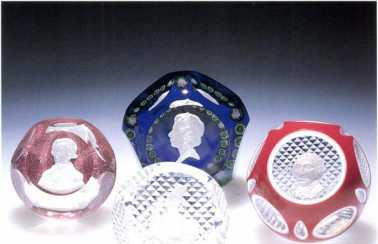

Baccarat Sulphides: Since the first Baccarat sulphide was produced in 1953, many other sulphides have been made, often in honor of American presidents and other notable world figures. The majority of these pieces were produced in limited editions. To mark the completion of a particular limited edition and to ensure that no further pieces are made, the cameo mold is ground down to destroy its face. In the case of the coronation sulphide, this was done ceremonially, with officials of the company and a notary in attendance.

Most of Baccarat’s early sulphides were designed by the French artist Gilbert Poillerat. Poill- erat, well known as a sculptor, medal engraver, and designer of jewelry, worked with Baccarat to rediscover sulphide-making techniques. It was Poillerat who was responsible for producing many of Baccarat’s most famous sulphide cameos.

Other sculptors who have produced sulphides for Baccarat include Albert David and Robert

5.12 lodern Baccarat sulphides

Cochet, both of whom worked as official sculptors lor the French Mint. Dora Maar (sometimes spelled Mar), a protegee of Picasso, also designed two sulphides for Baccarat.

Baccarat sulphides are usually produced in regular and overlay editions with a variety of ground colors and cutting designs. Baccarat’s regular sulphides are set in clear crystal and measure approximately 2 3/4″ in diameter by 1 1/2″ in height. Color grounds include red, blue, green, purple, and golden yellow. Baccarat overlays (single, double, or flash) are approximately 3 1/4″ in diameter by 2″ in height.

5.13 Baccarat Eustace Tilley sulphide

Correia Art Glass

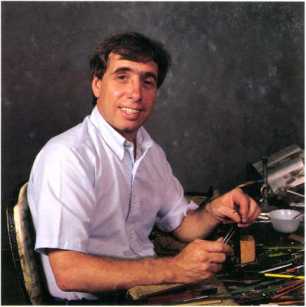

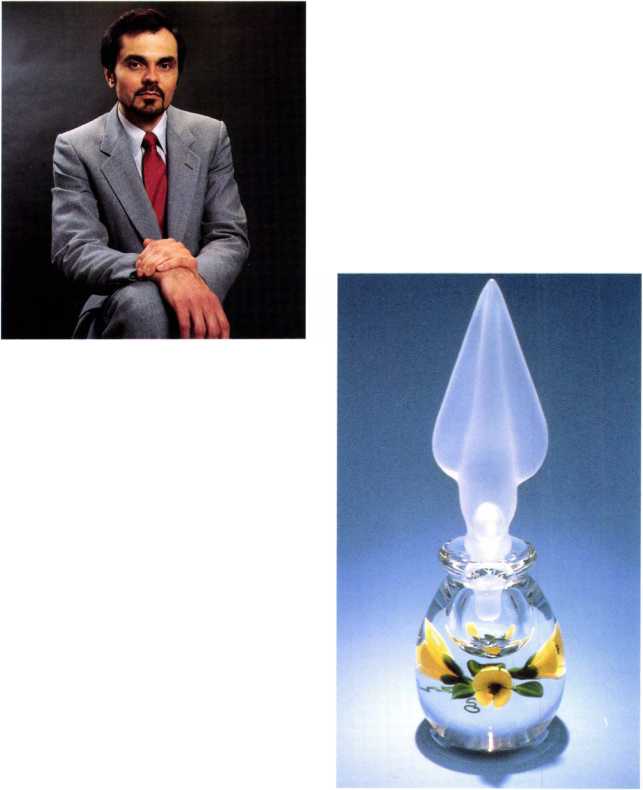

Founded by Steven V. Correia in 1974, Correia Art Glass in southern California is considered one of the finest art glass studios in operation today.

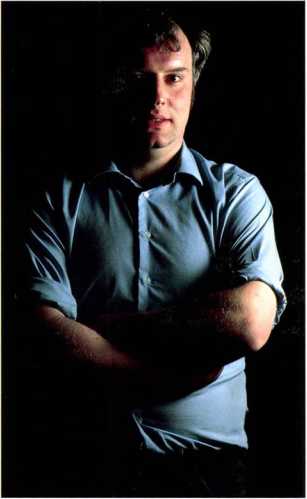

Born in San Diego on February 14, 1949, Steven Valentine Correia has been active in art since grade school. He was encouraged by his teachers and was enrolled in a gifted students program while still in high school. He attended San Diego State College and the University of Hawaii, and received an MFA from Hawaii. Originally interested in sculpture and ceramics, his work with three-dimensional mediums led him to glass work.

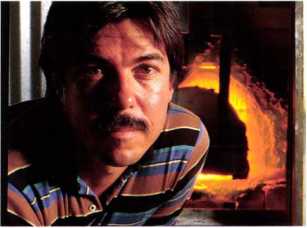

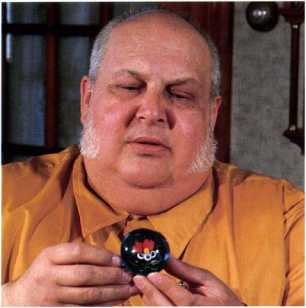

5.15 Steven Correia

Correia was fascinated by the iridescent lustres of the famed Tiffany Studios. The original techniques of Louis Comfort Tiffany were lost until Correia was able to recreate them. In recognition of his achievement, the Metropolitan Museum requested that he make tiles to restore a damaged mural from Tiffany’s Long Island mansion.

As the largest limited-production art glass studio in the country, Correia Art Glass has become famous for its art nouveau and art deco designs, iridescent color, anil exceptional quality. Pieces arc in the glass collections of the Metropolitan Museum, the Smithsonian Institute, and The Corning Museum, as well as in the White House.

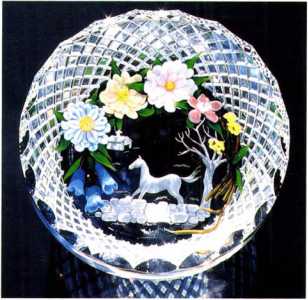

In the first years of production, Correia paperweights featured iridescent surface decorations. Later weights utilized lampwork designs, characterized by floral, animal, and aquatic scenes. Under

5.16 Correia molded snake weight

the influence of artist Chris Buzzini, who worked there from 1982 to 1986, paperweights were made in an unusual fashion. Each weight had a frosted outer surface with one large facet cut to reveal the interior design. The facet was usually placed at an angle for easy viewing when placed on display.

Correia Art Glass is now run by Correia family members. Steven has moved on to producing large-scale laser performances, like the permanent light sculpture he created in front of a building in San Diego. He is also making glass sculptures using cold working techniques.

Cristal d’Albret

As with Baccarat and Saint Louis, Paul Jokelson also encouraged Cristalleries et Verreries de Vi- anne of France to begin producing paperweights. The glass factory, which was founded in 1918 by Roger Witkind, began producingsulphideweights under the name “Cristalleries d’Albret” in 1967.

George Simon, a well-known engraver for the French Mint, was the first artist to create sulphide cameos for the factory. His pieces include the first four sulphides produced at d’Albret: Christopher Columbus, Franklin Roosevelt, King Gustav VI of Sweden, and John F. and Jacqueline Kennedy. This first Kennedy weight was only produced in a

small edition because the mold was broken during production.

1 he engraver (iilbert Poillerat, who had worked extensively with sulphides at Baccarat, began making sulphides for d’Albret in 1968. Poillerat was responsible tor modeling most of the sulphides in the d’Albret series, including a second piece commemorating the Kennedy’s.

D’Albret sulphides are produced in both regular and overlay editions. All weights of the same subject are finished with identical faceting designs and the same color or color combi nations. Weights are signed on the base with acid-etched letters arranged in a circle reading “cr. ai.bret—FRANCE.”

J Glass

“J” Glass

John Deacons, a skilled designer trained at the Edinburgh College of Art, formed “J” Glass in 1979 in Crielf, Scotland. The company derived its name from the enigmatic “J” signature cane found in certain nineteenth-centurv Bohemian weights. Deacons chose this same mark to honor the unknown creator of those ingenious weights and to identify his own skillful creations. The company produced paperweights in the classic style until it ceased operation in 1983.

“J” Glass paperweights include floral, insect, and reptile designs in lampwork as well as patterned millefiori motifs. Produced in limited editions of not more than 101 pieces, “J” Glass paperweights are signed with a blue “J” encircled by date numerals in red, green, and blue contained within a single cane.

5.20 “7” Glass founder John Deacons

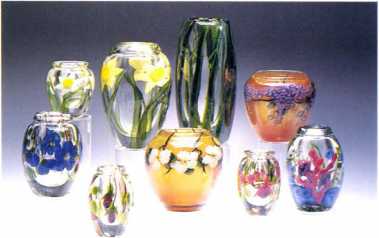

5.22 The artists of Lundberg Studios

Lundberg Studios

Located in the small coastal town of Davenport, California, Lundberg Studios has been producing quality paperweights since 1972. It first became known for its iridescent glass and art nouveau style. Later, its clear-encased weights with flower, bird, butterfly, and seascape motifs marked the emergence of a new form of paperweight.

James Lundberg, founder of the studio, first studied glassworking at California State University at San Jose during the late 1960s. Classically trained in ceramics, Lundberg worked for a time with Dr. Herbert Sanders, researching the Arabian smoke lustres.

A graduate tour took him to Germany, Italy, England, France, and Spain to continue studying glassmaking techniques. When he returned to the United States he joined with David Salazar and several other artists to create a small backyard glass studio in San Jose, California. At that time he became the first California glass artist to reproduce the colors and patterns of the highly acclaimed Tiffany Studios.

In 1972, with the encouragement of paperweight dealer L. H. Selman, Lundberg began ap

plying his iridescent glass techniques to paperweight design. A year later he moved to Davenport, California, to set up a cooperative venture with Mark Cantor and others. The facility included four melting furnaces, five glory holes, and two torchworking areas for paperweights, as well as a complete grinding setup and lamp shop. Lundberg, who worked his way through college as a technician, developed and built much of the glass studio’s equipment.

Lundberg Studios has consistently been staffed by glass artists working in the Renaissance studio tradition, with each contributing his or her unique skills to the glass process. Steven Lundberg originally trained as first apprentice to his brother James. Over the years he has worked in all aspects of glassmaking at the studio and is now a recognized glass master. David Salazar began as an apprentice in 1972. His torchwork helped to enlarge the paperweight-making focus of the studio. During the next eight years he worked primarily as paperweight decorator and designer. In 1974 Chris Buzzini joined the cooperative to offer his specific decorative skills. Daniel Salazar, who began as a pontil man for brother David and Buzzini in 1975, is now a master paperweight designer and decorator. In 1976 James Shaw joined the team primarily as cutter and polisher. George Shaw and Chris Bushman also lent their talents to the enterprise.

5.23 Lundberg Studios iridescent weight

5.23 Lundberg Studios iridescent weight

Out of the combined experience and expertise of all the artists, a new type of paperweight began to be produced at Lundberg Studios in about 1978. Called the California Paperweight Style (or torch- work), it represented a hybridization of two antique styles—the art nouveau Tiffany “ice pick” technique and the lampworking procedures of die French paperweight. It allowed for the direct application of complex three-dimensional imagery and enlarged the range of paperweights being offered by Lundberg. By 1978 the studio was producing crystal encased weights in the new style on a regular basis. To quote Lundberg, “My work and that of my studio is an outgrowth of my love and fascination with glass. The formulations, the special tools, and equipment have all been labors of love. I always look into the material for my inspiration. I am a glass man.”

Today Steven Lundberg, Daniel Salazar, and Samuel Sturgeon are the resident artists, but the influence of Lundberg Studios can be seen in the works of many of the prominent glass houses. Lundberg Studios continues to be a leader in the introduction of new designs and motifs. Currently

5.25 Lundberg Studios crystal-encased vases

it offers a variety of fine glass objects including vases, lamps, tiles, and jewelry’ in addition to its full line of paperweights. Many of these pieces are included in major museum collections—The Corning Museum of Glass, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Smithsonian Institution.

Each Lundberg piece is signed with the studio name, artist’s name, date, and number.

5.24 Paperv eights front Lundberg Studios

Orient & Flume

Glass artists Douglas Boyd and David Hopper studied at California State University in San Jose during the late 1960s, where they took part in some of the earliest college classes offered in glass- blowing on the West Coast. After graduating with Master’s degrees in glass, Boyd and Hopper traveled extensively throughout Europe studying glass and glassmaking techniques.

In 1972 the two artists established Orient & Flume as a small glassblowing operation in Chico, California. In an interview published in American Art Glass Quarterly, Winter 1983, Douglas Boyd discussed the studio’s name:

The first house where we blew glass in Chico was located between Orient and Flume Streets. We liked the sound of a combination of the two names and chose it for the personal meaning to us. However, the word orient also means a pearl of great beauty, value, luster—anything valuable and beautiful. Flame is derived from a French word that means to flow. Our glass designs are flowing and fluid. So the words orient anti flume, in effect, define the glass.

Orient & F lume has grown from a two-person operation to a glassworks with a staff of twenty people. It can be described as both a studio and a factory in that it has the required furnaces and can dependably produce glass in quantity. The facility runs eight colors regularly and has the capacity for

- 5.26 The artists of Orient & Flume

- 5.27 Orient & Flame mallard aright

twenty. Still, it is small enough to allow each artist the chance to work and create as an individual.

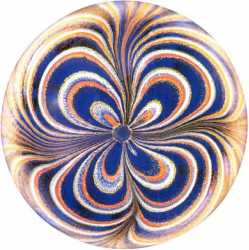

Orient & Flume’s glassworkers successfullv synthesize glass styles and techniques from many different time periods and parts of the world with their own contemporary artistic interpretations. The company developed its reputation producing brilliant iridescent glass paperweights and other objects with art nouveau motifs and elaborate surface decoration. Early paperweights were made using the torchwork, or hot glass decorating technique, in which molten threads or dots were applied to the surface of a piece and then manipulated into a pattern. Its product line later evolved to include lampwork decorations. Coming from Lundberg Studios, artist Chris Buzzini brought with him new techniques in this area when he joined Orient & Flume. The result of this blending of styles and techniques is a rich and innovative approach to paperweight design. Some limited edition pieces, for example, have been crystal- encased weights w ith fumed iridescent grounds of various colors that used millefiori and torchworked glass for details.

Orient & Flume produces its own glass and creates its own colors. The sand, which comes from pure deposits in Oklahoma and Texas, and the other ingredients, some of which come from Russia, South Africa, and Israel, are melted every night for use the following day. A studio approach is used for most pieces, in that a piece is created from start to

ORIENT & FLUME

finish by one person. I Iowever, the shop structure is used in iridescent pieces, so that the gathering, decorating, finishing, and fuming are each done by the person most skilled in that area.

Orient & Flume glass is represented in the permanent collections of The Corning Museum of Glass and the Chrysler Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia. Pieces may be seen in England, Scotland, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, Africa, and South America. The company was also honored with a commission from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to produce a series of tiles for the restoration of the home of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Orient & Flume paperweights are signed, dated, and numbered on the base.

- 5.29 Orient & FI tune iridescent flower zvei

- 5.30 Perthshire founder Stuart Drysdale

Perthshire Paperweights

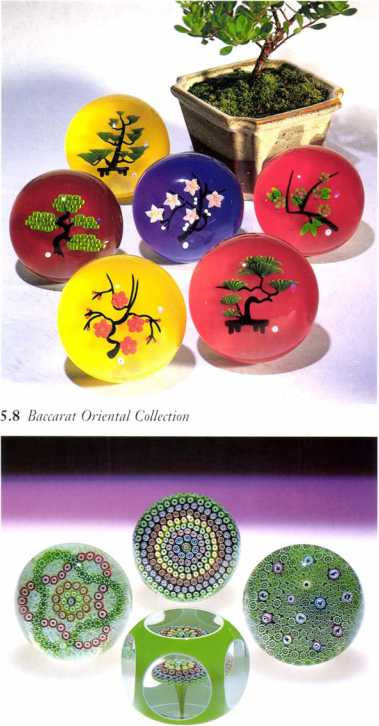

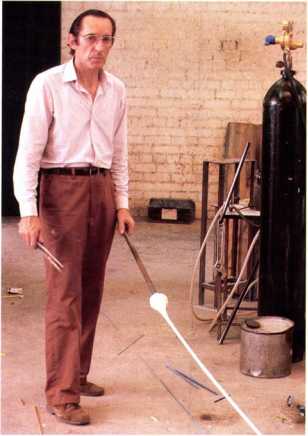

Perthshire Paperweights is one of the few factory- size operations in the world devoted exclusively to making paperweights and paperweight-related objects. Founded in 1968 by Stuart Drysdale, a country lawyer and businessman, the factory is located in Crieff, a small farming community in central Scotland.

Drysdale first became familiar with paperweight manufacture while managing two other glass factories in Scotland—Vasart Glass and Strathearn Glass. Both factories produced small numbers of paperweights but the pieces were extremely simple and crude in craftsmanship and design. In 1967,while working at Strathearn, Drysdale was introduced to the history and sophisticated techniques of antique French paperweights through an American magazine article. lie was intrigued with the possibility of creating paperweights equal to those made during the classic period.

In 1968 Drysdale and the master glassblowers of Strathearn left that company and formed Perthshire Paperweights. For the first two years the operation was located in an old schoolhouse that had been converted into a makeshift factory. In 1971 Perthshire moved into a newly constructed, modern factory on the outskirts of Crieff.

About three-quarters of a ton of glass is produced each week at Perthshire. The primary ingredient of Perthshire’s glass is white sand from northwest Scotland.

The Perthshire factory employs about thirty craftspeople who work together designing and

5.33 Perthshire craftsman and finished articles

producing paperweights. Millefiori and lampwork designs are created by the glassworkers themselves and experimentation is encouraged.

Stuart Drysdale said of Perthshire’s operation: “If we’ve got one secret at all to our success today, it is that rarely can a person come along and say, ‘That’s mine—I made it.’ Other hands have been involved. In other words, we are really doing what the traditional famous factories in glass and china did—developing a team and a factory name.”

Perthshire Portrait Canes: In 1972 Perthshire began including portrait canes in many of its regular and special edition paperweights. Portrait canes may resemble silhouette canes, but they are made in an entirely different way. A number of very thin glass rods are arranged like a mosaic in a mold, heated together, and then stretched. Perthshire’s first portrait canes were solid, single color, black or white designs. In 1974 the factory produced its first color portrait canes.

Perthshire portrait canes include:

| Sailboat | Scottie dog |

| Pelican | Flowers |

| Butterfly | Thisde |

| Polar bear | Angel |

| Cat | Christmas tree |

| Robin | Sleigh |

| Owl | Reindeer |

| Donkey | Santa Claus |

| Ostrich | Church |

| Candle | Crown |

| Swan | Penguin |

| Airplane | Pelican |

| Rooster | Duck |

| Squirrel | Jumping rabbit |

| Nursery rhyme | characters |

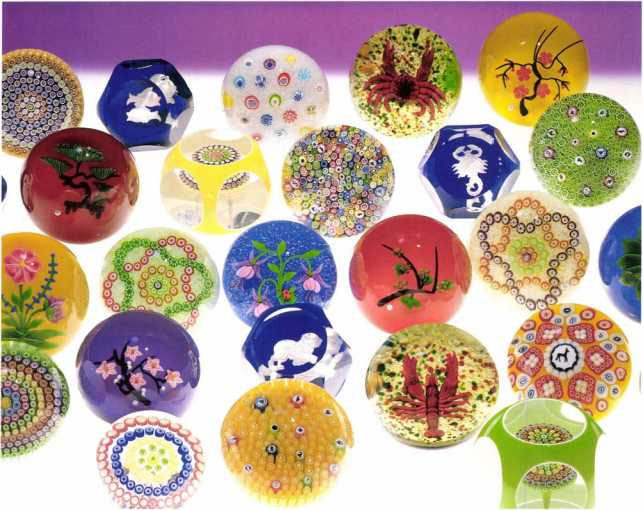

Editions, Signing, and Dating: Perthshire regularly issues three types ol paperweights: the special yearly collection; regular limited issues; and decorative weights. In addition, Perthshire’s craftspeople occasionally make one-of-a-kind pieces and some paperweight-related objects.

Perthshire’s special yearly collection is made up of new designs created for a specific year, produced as limited editions, and never repeated. These pieces include a cane containing the “P” initial or a “P” cane with the year of issue. In some instances the initials of one of the craftsmen is etched with a diamond stylus on the base of the piece. Perthshire’s regular limited issues are weights produced in small quantities for a specific number of years. Some of these pieces are signed alphabetically, with the letter “A” representing 1969, “B” 1970, and so on.

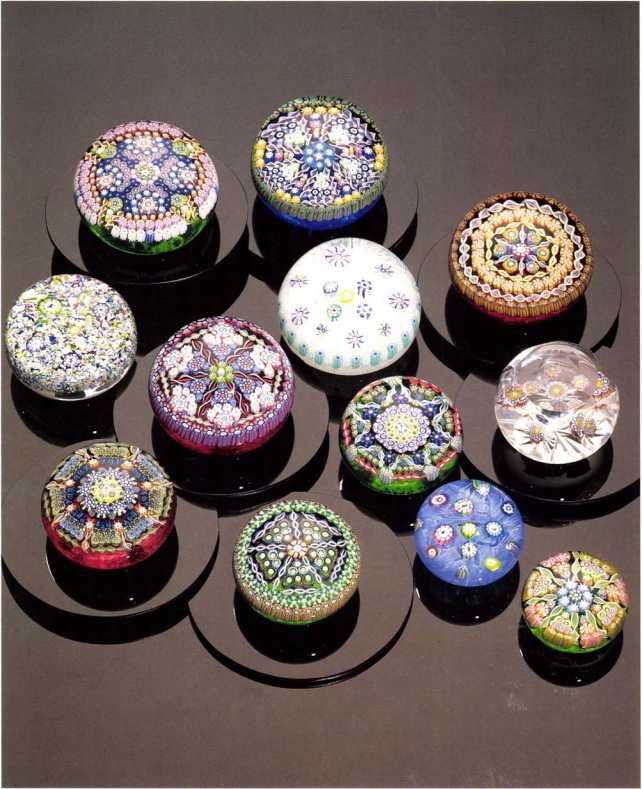

- 5.36 Perthshire Special Yearly Collection

Perthshire’s decorative weights, which director Stuart Drysdale calls his “bread-and-butter weights,” help finance the production of the limited edition pieces. Though not regarded as collectors’ items, they are considered to he the finest weights of their type on the market. They generally display concentric rings of millefiori canes that are often divided by a wheel and spoke arrangement of thin spiral canes.

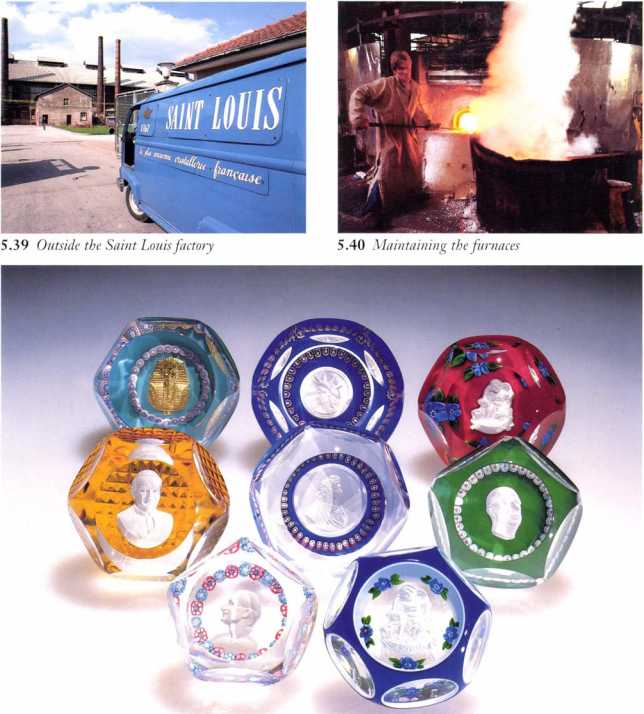

Saint Louis

In the early 1950s, at the special request of Paul Jokelson, Saint Louis began experimenting with paperweight making after a lapse of over eighty- five years. Paul Gossmann, a talented young glass- maker at Saint Louis, was given the job of rediscovering the lost techniques. In The Ait of the Paperweight—Saint Louis, Gossmann described his early experiments:

Finally, in 1951, the shop supervisor nominated me for a thrilling assignment: try to remake, identi- ca lly, nineteenth-century’ paperweights. I was eighteen years old when a long period of research and testing began for me. With the aid ot Louis Lutz, the first rods were produced, and after a few weeks, the first paperweight reflected the light of day. However, the quality level was low. After a few months, progress was made in quality, and production was just about to begin. Then I made my first lampwork flowers, dahlias. Two years later it was overlays, and then the Queen Elizabeth of England sulphide. I knew many secrets remained, especially the one concerning the upright bouquet. Not until I saw an

old bouquet broken in two, was I able to recover the lost secret.

Gossmann spoke also of the personal satisfaction involved: “I rediscover each year the pleasure of inventing for the new collector. When a paperweight is a success, I feel an intimate joy, a feeling of creation.”

The process of producing sulphides also remained a mystery to Saint Louis glassworkers until a nineteenth-century piece was broken open and examined. After analyzing the chemical composition of the enclosed cameo a test weight was produced. This test piece, which displayed a cameo of the Duchess of Berry, was made in 1952.

In 1953 Saint Louis issued its first twentieth- century’ paperweight. This limited edition sulphide was made to commemorate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The sulphide cameo was sculpted by Gilbert Poillerat and Saint Louis glass- blowers Paul Gossmann, Albertjonas, Louis Schilt, and Gerard Stenger were involved in its inaugural production.

Twelve hundred and twenty-sixweights were produced, with each piece bearing the circular inscription “Couronnement 2.6.53 Saint Louis—Prance.” Several variations were made within the edition:

Twelve hundred and twenty-sixweights were produced, with each piece bearing the circular inscription “Couronnement 2.6.53 Saint Louis—Prance.” Several variations were made within the edition:

Clear crystal 47

Clear crystal with millefiori 132

Turquoise ground 60

Turquoise ground with millefiori 324

Red ground 71

Red ground with millefiori 118

Dark blue ground 57

Dark blue ground with millefiori 290

Black ground 2

Topaz ground with millefiori 2

Red jasper ground 61

Blue jasper ground 62

Between 1952 and 1955 Saint Louis produced a limited number of pieces (300-400) in addition to the coronation sulphide. These weights w ere made primarily to satisfy American requests and w’ere not always dated. Lampwork motifs included clematis, daisy, pansy, cherries, fruits and vegetables on lace; a millefiori piedouche and a millefiori up

right mushroom with an overlay were also made.

In 1965 Saint Louis produced a faceted butterfly weight that utilized both lampwork and millefiori techniques, a snake weight, and an upright lampwork bouquet. In addition, the factory began production of a small series of sulphides.

Although experimentation with paperweight making was begun in 1951, production during these early years was sporadic. Itwasnotuntil 1970 that Saint Louis made a commitment to produce paperweights on a regular basis. Since that time the factory has issued a set of limited editions each year. It was decided that the modern weights w’ould include a date cane and the initials “SL.” The technique, design, color, and size of a modern Saint Louis paperweight have their origins in nineteenth-century artistry. Tradition has been perpetuated in contemporary Saint Louis weights. In the following excerpt from an essay, Yolande Antic, the coauthor of the first French book on paperweights, Les Presse-Papiers Franqais de Cristal., discusses modern Saint Louis weights in relation to the weights of the past:

To discover the manufacturi ng process—the techniques which had permitted the creation of these small masterpieces of the nineteenth century’ manual arts—appeared to he a long shot. It has been achieved, and the glassmakers of Saint Louis prove that their skill is equal to that of their predecessors. What remains to be said about contemporary’ production? Were it not for the trademarks which differentiate them, no criterion of quality’ would allow one to distinguish classic and modern editions.

Millefiori canes, silhouette canes, filigree grounds and multicolored torsades are comparable in all respects; florets, upright bouquets, fruits and twisted colored strands reproduce those ol the past to the point of confusion. At first glance, confusion is possible; nevertheless, a more careful examination permits one to determine the characteristics of modern specimens.

There is, first of all, a question of size and of brilliance of colors. The nineteenth-century paperweights, in general, are smaller than those of recent issue; they are slightly swelled around the base, slightly flattened and in the shape of a cup. Numerous cuts, often in little facets, further diminish nineteenth-century paperweights compared to the fuller

size of modem weights.

More intense colors replace the delicate, slightly acidulated hues of antique paperweights; three rather strong shades of blue and two greens replace the very soft medium blue, lemon yellow and tart absinthe green of the past, and a warm, deep blood red introduces a totally new note. The mauve, coral rose and orange tones of the grounds in flowered spheres compose the palette of distinctive modern production.

…. Finally, one must pay particular attention to the triple spheres called “overlays.” What a shame

that the French expression, “boule doublcc ou triplec couleur,” which is so precise, should he sacrificed to the Anglo-Saxon term. So it is that a very traditional, footed “vase for feathers” is modernized as a “penholder,” and that a “darning egg,” in a time when one no longer darns, is presented as a “handcooler.”

I lowever, what good is it to complain? Isn’t it better to smile and pat oneself on the hack that a simple trick of the language permits us—although the function is royal in origin—to continue to create for our own delight these few charming objects . . . fortunately of no other use?

5.44 Whitefriars glassworker

Whitefiriars/Caithness

Whitefriars Glass, a factor)’ in London that some believe had been producing millefiori paperweights since about 1848, closed its doors in 1981. Immediately thereafter, Caithness Glass of Scotland purchased the complete stock of Whitefriars millefiori canes, the right to use the company’s name and logo, and its extensive color library, which included formulas for several thousand glass colors. Since that time Caithness has been producing paperweights under the name of Whitefriars. Y\ “eights showing the name Whitefriars made after 1981 were made at the Caithness facilities in Wick and Perth, Scotland.

These Caithness/Whitcfriars weights, which hear no similarity to the original Whitefriars weights, still include the traditional Whitefriars signature cane of a white-robed monk in silhouette and number canes indicating the year of manufacture. There is no evidence that Caithness has included the millefiori canes purchased from White- friars in any weights it has produced.

Founded in 1960, Caithness Glass also produces paperweights under its own name and the name Edinburgh Crystal. Many of the designs used in the Edinburgh/Caithness pieces closely resemble Perthshire millefiori motifs. However, the canes in the Edinburgh/Caithness weights are less refined than Perthshire canes, and the workmanship anti glass not always of the same quality.

Harold Hacker

Harold Hacker began working in glass factories in West Virginia at the age ot thirteen. During the late 1930s he moved to the Los Angeles area, where manyofhis former West Virginia coworkers had also settled. There he worked for the Technical Glass Company and Douglas Aircraft. After serving in the armed forces in World War II, Hacker established a glass concession at Knott’s Bern’ Farm, a Los Angeles amusement park. He built up a successful business making intricate glass figures produced by manipulating colored and clear glass rods over a torch.

In 1966 Hacker read about a paperweight that had sold at auction for more than Si4,000. The article suggested that weight making was a lost art and that no one could duplicate antique weights. With his extensive glass and lampworking experience, Hacker set up a small furnace and workshop. I le encased his lampwork setups in clear glass gathers from his small furnace and distributed them, along with weights by West Virginia artist A. F. Carpenter. Hacker’s weights include lampwork flowers, fruit, snakes, salamanders, and many other kinds ol animals.

Harold Hacker’s paperweights are signed in script with a diamond-tipped pen in one of three ways: “H. J. II.,” “II. J. Hacker,” or “Harold J. Hacker,” with the full signature indicating the higher quality weight.

LOTTON GLASS STUDIO

5.48 Outside the Lottott studio

Charles and David Lotton

A fascination with iridescent glass led Charles Lotton to build a small workshop with a furnace and an annealing oven, providing him with space to experiment with glass and glassblowing. In 1973 he began working full time to produce paperweights and vases in the art nouveau style. Many of the designs he used were from the Egyptian, Oriental, Islamic, and Grecian periods. One of his greatest accomplishments was the discovery of the formula for mandarin red glass.

- 5.50 David Lotton

- 5.50 David Lotton

Paperweights made by Charles Lotton are not finished on the bottom and show a rough pontil scar near the script signature.

From the age of ten, David Lotton helped his father, Charles, in his art glass studio in Illinois. While working as his father’s assistant, he began experimenting with making paperweights on his own. By 1975, when he was fifteen, he was producing his own weights.

David Lotton’s weights are primarily iridescent surface-design weights with floral motifs. All his pieces earn- his signature and the date etched on the base.

5.51 William Manson “Arctic Encounter” weight

William Manson

At the age of fifteen, William Manson joined Caithness Glass in Scotland, where he was given the opportunity to be an apprentice to master glassblower Paul Ysart. Ten years later, Ysart left the company and Manson took over the designing of limited edition paperweights for Caithness.In 1979 Manson opened his own glassworks just outside of Glasgow. Two years later he closed the works and went back to work for Caithness. His pieces include lampwork flowers surrounded by garlands of millefiori canes, salamanders set on rocky grounds, fish, swans, and several other motifs.Manson weights are signed with a signature/ date cane and numbered on the base. Each design is limited to 150 pieces.

Michael O’Keefe

Working in two converted storefronts in Seattle’s south end, artist Michael O’Keefe is creating some of the most unusual and beautiful contemporary paperweights. Reminiscent of Dominick Labino’s early work, his elegant weights display soft-hued forms and shapes caught in delicately colored crystal. His fascination is with the transparency of glass. Working with the space inside the surface, the paperweight becomes the form, the area to explore and work within.

Initially a student of photography, O’Keefe began taking glass classes whi le studying at the Center for Creative Studies in Detroit. After receiving his BFA in photography in 1976, he worked for two years at the Poultry Glassworks in downtown Detroit. Poultry’ Glassworks deals exclusively with the technique of silver veiling, and all of O’Keefe’s paperweights utilize this relatively new process.

The silver veiling process involves melting silver and glass together. The variables of the furnace atmosphere bring the silver to the surface of the glass. Critical timing at each stage of heating, reducing, and cooling determines how the silver will fall. Different elements in the formula also cause the silver to react in different ways. When the glass is pulled and twisted, the silver causes it to change color—from brown to yellow and from yellow to blue. Unlike many studio artists, O’Keefe makes his own glass, so that he can get the perfect glass for his purposes. Thus his unusually subtle and delicate colors are the result of the specific ingredients used in his batch, or glass mixture.

5.55 O’Keefe inspecting a weight

While in the Navy, O’Keefe spent three years in Japan, where he gained an appreciation of and love forjapanese design. His current work subtly reflects that aesthetic: external simplicity with internal complexity and depth. The inner forms are soft and suggest continuous movement; the outer shapes elegantly frame this movement. Fire polishing and careful grindingcomplete the impression of fluidity, eternally caught and held.

O’Keefe’s weights are signed and dated on the bottom with a diamond stylus.

Parabelle Glass

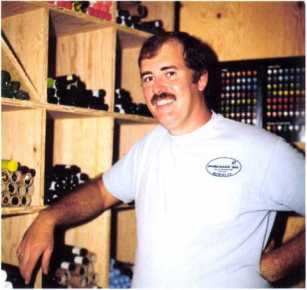

In 1983, with the help of his wife Doris, Gary Scrutton began making paperweights in a small studio in hack of their home in Portland, Oregon. Using the name Parabelle Glass, the Scruttons are the only studio artists in this country concentrating exclusively on the production of millefiori weights.

Gary first began working in glass in the 1940s. His Portland-based glass business produced stained glass for churches and restaurants throughout the United States. In 1981 Gary began developing a glass studio at home, and in 1983 he sold his stained glass business to his two sons. Then he began making millefiori paperweights, which, he says, hold so much more mystery for him.

With only the most general information available, Gary spent the first year in his new studio unraveling the mystery—experimenting with the making of glass and the development of techniques. Unlike the big factories, he had no archives, no resources, no history to help him. He worked diligently to overcome the host of problems involving equipment, design, and the making of colors and canes.

5.56 Gary and Doris Scrutton

dent in their close packed millefiori, garlands, and basket motifs. Of special note is the unique pansy cane, a Parabelle exclusive. Gary has also designed eight silhouette canes, including a squirrel, elephant, rabbit, dove, butterfly, and rooster.

Parabelle weights are signed “PG” in a cane within the design.

Doris Scrutton primarily creates the paperweight designs, but she is also the walker in stretching the millefiori canes. In the traditional manner, pontil rods are attached to each end of a thick heated cane. She then walks—or runs—stretching the glass rod from forty to one hundred feet, depending on the temperature of the glass and the diameter desired.

- 5.58 Gary Scnitton blocking it weight

- 5.59 Outside the Parabelle Glass studio

In contrast to many studio artists Gary makes all his own colors, purchasing his raw materials from a local supplier. In this way he can have everything in his control. lie has also developed a highly sophisticated glass studio with computers regulating the temperatures of the furnace and the glass formulas. The main furnace holds two hooded pots, very similar to what the French use, and two smaller pots for colors. I Ie melts about 160 pounds of crystal each week.

The Scruttons have been greatly influenced by French weights, particularly Clichy, in terms of paperweight style, color, and design. Their contemporary use of classical motifs is especially evi-

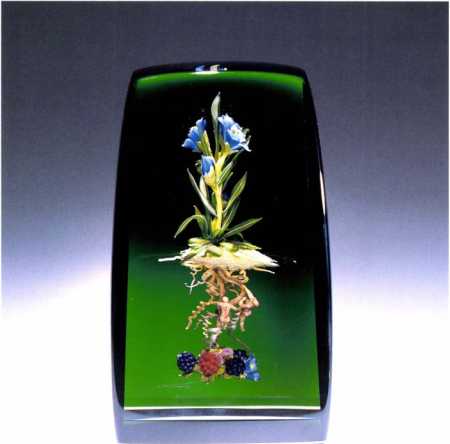

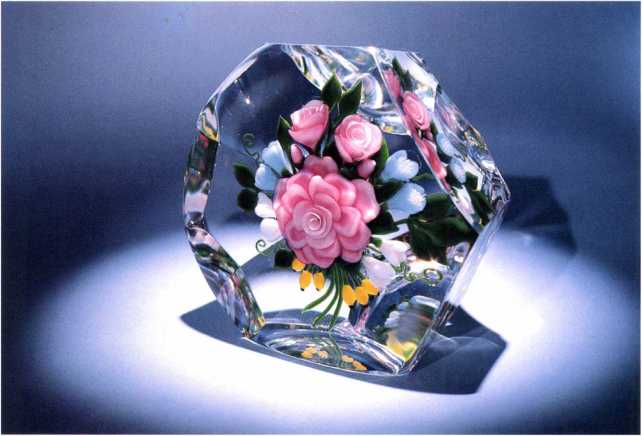

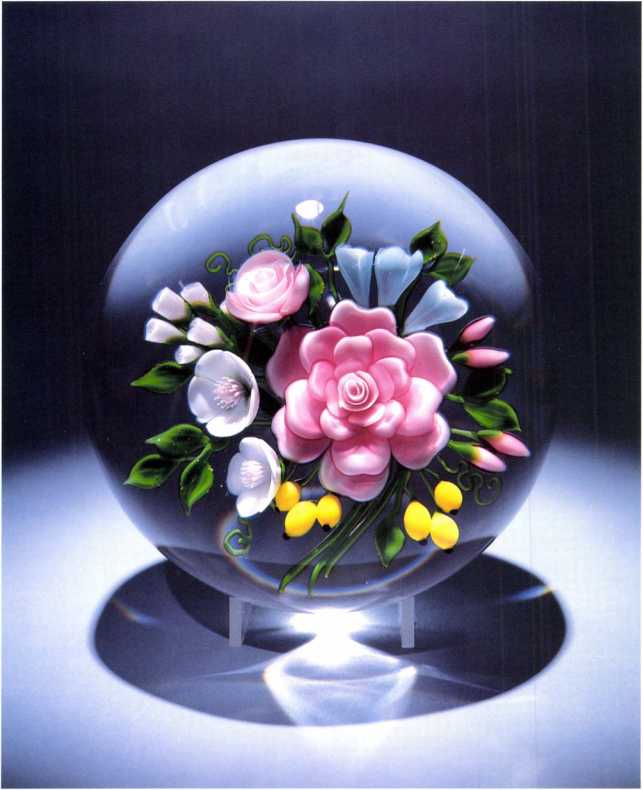

David Salazar

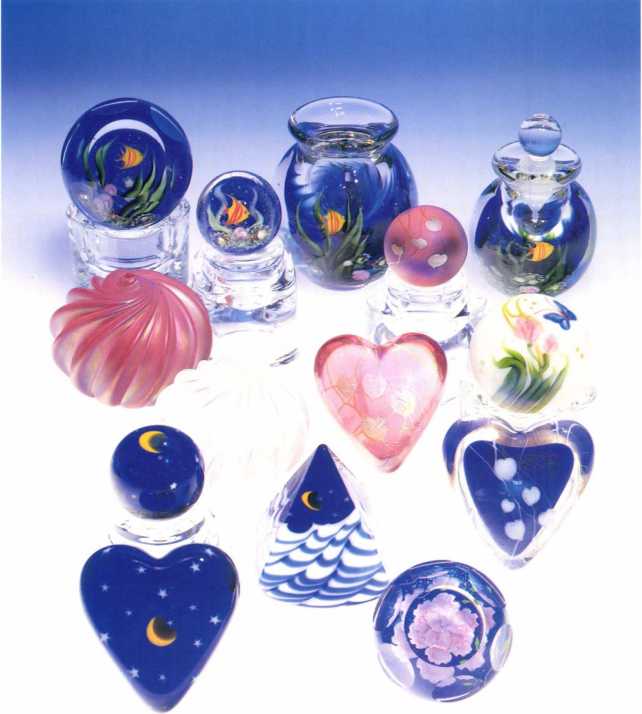

David Salazar is an artist of unbounded creativity and enthusiasm. Few other furnace artists can consistently offer such a wide range of styles, colors, sizes, and design motifs. Salazar calls himself a “one-man factory.” As this factory he melts his own glass, makes his own colored glass, pulls his own rods and millefiori, and makes designs that continue to expand the possibilities of creative glass paperweights.

David Salazar was first introduced to glass in 1972 while studying at California State University at Sanjose. He chanced to meetMarkCantor, who was then sharing a studio with James Lundberg. Salazar was fascinated by the hot glass process and was offered a job as apprentice to Cantor. At the same time he met Lawrence Selman, who expressed a desire for the two artists to develop a line of paperweights. His interest was in design, and the medium of glass offered the perfect format for his creative skills and artistic vision.

Salazar worked for ten years at Lundberg Studios, becoming its chief paperweight designer and decorator; at times working with Chris Buzzini andjames Shaw; and introducinghis brother Daniel to the world of paperweights. He has also workedwith Correia Art Glass and with Zephyr Studios. In 1985 he built his own studio in Santa Cruz, California. There, with two furnaces, three color pots, two glory holes, and a state-of-the-art air/gas mixer, he is recreating in paperweights the beauty and variety of the world he sees. Undersea life, the night sky, the moon and the waves, surface design florals, romantic hearts, and swirls are all within his wide range of expression.

- 5.61 David Salazar

Salazar employs some of the usual techniques, especially torchwork and millefiori. But his style is a more contemporary art nouveau style, using flowing lines and designs often set in relief. Recently he has concentrated on miniature and petite weights.

Salazar’s weights are signed and dated in script on the bottom.

5.63 Paperweights and other objects by David Salazar

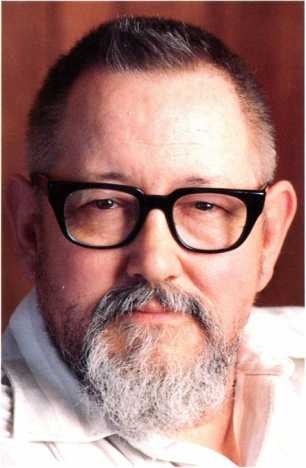

5.64 Paperweights by Paul Ysart Paul Ysart

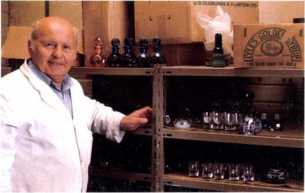

Born in Barcelona in 1904, Paul Ysart is considered one of the most important contributors to paperweight making in the twentieth century. A paperweight artist since the 1930s, Ysart was one of the first contemporary craftsmen to rediscover and refine techniques used in making weights.

Both Ysart’s father, Salvador, and his grandfather were glassblowers in Spain. Just prior to World War I, Salvador moved his family to France, where he worked as a master glassblower in Lyon, Marseilles, and Paris. In 1915 the family moved to Scotland, where Salvador worked at the Edinburgh and Leith Flint Glass Works. It was there, at the

age of thirteen, that Paul, Salvador’s oldest son, began training as his father’s servitor. In 1922, Salvador was offered a position at John Moncrieff Limited Glass Works in Perth, Scotland, a firm specializing in laboratory glassware and apparatus. Salvador brought along Paul and his three other sons, Vincent, Augustine, and Antoine, as apprentice glassblowers. While at Moncrieff, the Ysarts created the “Monart” line of colored glassware, which was manufactured from 1925 to 1960 and was widely exported to the United States.

During his early years at Moncrieff, Paul, with the help of his family, began experimenting with paperweight making. Some of the early weights

5.65 Paul Ysurt

made by Paul and his family were marketed by Moncrieff and today occasionally turn up bearing a Moncrieff label. By 1938 Paul was creating quality7 paperweights, which were finding their way into important collections. Two examples of his early work, both featuring butterfly motifs, were illustrated in Evangeline Bergstrom’s 1940 classic, Old Glass Paperweights.

In 1948, Salvador and his sons V incent and Augustine started their own business called Ysart Brothers Glass at the Shore, Perth. Paul continued on at Moncrieff, where he created some of the finest paperweights made since the nineteenth century. In 1963 he took a job as training officer with Caithness Glass in northern Scotland. On his own time he continued to make paperweights, and he created over twenty different designs before he left Caithness in 1970.

In 1971 Ysart started the Paul Ysart Glass Company in Wick. Here he could specialize in paperweights and other glass objects produced in very7 limited editions. Since his retirement in 1979,

5.66 Paul Ysart srwimmiug fish weight

Ysart has continued to make a few weights.

Over his fifty7 years of paperweight making, Ysart has produced a range of millefiori and lampwork designs set on clear, colored, and lace grounds. ()ne ofhis most popular lampwork motifs is a hovering butterfly, shown on a number of different grounds. Other subjects include clematis- type flowers, lacy or decorated snakes, dragonflies, ducks, and swimming fish.

Most of the paperweights made by Paul Ysart contain a small “PY” signature cane either in the design or on the base of the piece.

Lampwork

Renewed interest in paperweights by the great glass factories in Europe and America served to inspire a number of individual artists. They were encouraged by the growing market, but even more by the challenges to duplicate and expand on designs and techniques of the past. Together with the contemporary glass factories, these artists are responsible for the current renaissance in paperweight making.

In the late 1940s a lampworking technique was developed to produce Krench-stvle paperweights without using a furnace. The major distinction is the origin of the glass. Factories make their own glass in large vats or furnaces, whereas lampwork artists begin with solid slugs of glass that are made commercially. The slugs are melted down and manipulated into shape using small gas burners or torches.

This section includes most of the artists using the lampworking technique. Many ol these artists gained their skill and expertise in glass working as scientific and industrial glassblowers in factories producing decorative glass. Some worked as novelty glass makers. From a design perspective, many of these contemporary studio artists are expanding on the more traditional styles and motifs. They are creating their own unique designs rather than working within the style of the traditional French weights of the classic period.

Some of the master artists represented here are entering into entirely new areas of creative expression. Paul Stankard has brought out the cloistered botanical. Delmo Tarsitano has introduced a nonmagnifying rectangular form to replace the traditional dome. Lundberg Studios is producing crystal-encased paperweights anil vases in their ow n California Paperweight Style.

New areas emerge as these artists reach the edges of creativity and then expand beyond them. The listing is not exhaustive; hut the artists included here are the ones you would most likely encounter as you pursue the paperweight in its finest forms.

5.68 Rick Ayotte

Rick Ayotte

Roland (“Rick”) Ayotte, a native of Nashua, New I lainpshire, continues to be the only artist making ornithologically accurate motifs in paperweights. His skill and artistic expression have grown to include naturalistic settings that lend realitv and depth of field to the birds they surround.

- 5.69 Rick . lyotte faceted pansy and ladybug weight

- 5.70 Rick Ayotte Christinas weights

Ayotte has been keenly interested in birds since he was in high school. During that time he charted migratory bird groups and studied their food and eating habits. He also began carving life-size birds from wood.

Ayotte studied at Lowell Technological Institute and later worked as a scientific glassblower in Nashua. In 1970 he started his own business, Ayotte’s Artistry’ in Glass, which specialized in solid crystal, weave, and hollow glassware gifts. In 1976 he was asked to create two life-size lilacs for the White House Christmas tree. The project proved to he quite an undertaking, with each lilac containing over 200 separate flowers.

5.72 Rick Ayotte fruit and flower weight

While working as a scientific glassblower, Ayotte became acquainted with Paul Stankard, who worked at the same company. It was Stankard who first encouraged Ayotte to try’ his hand at paperweight making. Stankard had noted the lack of bird subjects and asked Ayotte if he would be interested in filling the gap. In 1978 the first Ayotte weights appeared on the market. For Ayotte, paperweights offer a creative challenge as well as an opportunity’ to combine skill and expertise in glass with a long-time interest in ornithology.

In his earlier weights, Ay’otte’s birds were set in simple surroundings and encased in clear crystal. His later work grew to include intricate foliage, berries, flower blossoms, butterflies, nests, and the use of color grounds. Most of Ayotte’s pieces depict birds in their natural habitats. Ilis use of lampwork flowers and vegetation is extensive.

Ayotte has also developed a compound layering technique, which involves creating two separate encased layers within a weight. This has given him the ability to achieve an unusual sense of depth and realism in his work.

In speaking of his work, Ayotte say’s, “When you look at a paperweight, you should get something— y’ou try’ to get a feeling. It’s more than making it real and color-coordinated. You have to get a feeling in a little sea of color.”

Ayotte produces paperweights in editions of from twenty-five to seventy’-five pieces. He signs his work with an engraved “Ayotte” plus edition number and size on the base.

Bob Ban ford

Bob Banford’s classic-style paperweights have been greatly influenced by French paperweight design. His pieces feature a wide range of finely crafted lampwork subjects including single flowers, intricate upright and flat bouquets, bumblebees, dragonflies, and salamanders.

Bob’s fascination with glassmaking is very’ much in keeping with the long-time interest his family’ has had in the profession. Bob’s grandfather knew Emil Larson, an American glass craftsman well known for his crimped rose paperweights. Bob’s father worked as an antique glass dealer for many years and often did business with paperweight makers Fete Lewis and John Choko from Millville. Also, the Banford family has its roots in the Vine- land, Xew Jersey area, a region rich in glassmaking history and tradition.

After high school Bob worked as a scientific glassblower for a year and a half. I le began demonstrating novelty glasswork and in his spare time experimenting with paperweight making.

In 1971 Bob and his father Ray Banford, who had also become interested in the craft, began seriously producing paperweights. Since that time Bob and Ray have worked together in a small studio behind their family home in Hammonton, New Jersey. They share ideas and techniques, butwork as independent craftsmen and have each developed distinct and individual styles.

5.73 Boh Banford

After Charles Kaziun, the Banfords were the next to develop the making of overlay paperweights with a torch. It is a more difficult process, more precise, with a much higher failure rate than overlays made out of a tank. They have also produced distinguished basket and gingham cutting designs. Most of their intricate cutting is done by Ed Poore, considered one of the best paperweight cutters in America.

Bob’s paperweights are in a number of private and public collections including the Smithsonian Institution, The Corning Museum of Glass, Wheaton Village, the Chicago Art Institute, and the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum. Each of his weights contains a signature cane made up of a red “B” in a white ground surrounded by a blue rim.

5.74 Bob Banford salamander weight

5.76 Ray Hanford Ray Banford

Ray Banford became intrigued by the idea of making paperweights after visiting the workshop of Adolph Macho, an elderly Czechoslovakian glass craftsman who worked in Vineland, New Jersey. Watching Macho create a paperweight, he became fascinated with the process. A visit to The Corning Museum also served as inspiration. Thus, in 1971, Ray and his son, Boh, began making paperweights.

Ray’s paperweights include bouquets of lampwork irises, lilies-of-the valley, and morning glories, as well as paperweight-style buttons and pendants.Occasionally Rat– and Boh Banford have produced “combination weights,” in which lampwork elements made by each craftsman are encased within a single weight. These rare pieces include signature canes by both artists.

5.76 Ray Hanford Ray Banford

Most ot Ray’s work is identified with a cane with a black “B” on a white ground; however, many of his early weights contain signature canes in a variety of color combinations.

Chris Buzzini

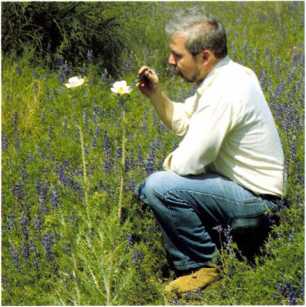

Paperweight maker Chris Buzzini attributes his lifelong interest in art to the fact that he was born and raised in Yosemite National Park, one of the most magnificent natural environments in the world. One of his clearest childhood memories is sitting on a rock and painting landscapes for hours. Having lived in that natural beauty, he carries impressions for a lifetime. And he carries a fascination with and attention to detail that shine through all his work.

5.80 Chris Buzzini azalea bout/net

Buzzini began college as a student of architecture. While taking a drawing class he discovered the ceramics department, which eventually led him to the school’s glass program. He became fascinated with the medium and entered die glass department at Chico State.

Buzzini set up a glass studio in his home where he could experiment on his own. In 1972 he became a small-interest partner in the newly formed art glass studio Orient & Flume. From there he went on to work at several prominent art glass studios in California, including Lundberg Studios and Correia Art Glass. I le also had the rare opportunity’ to work with a patron, Gaylord Evey, who was instrumental in setting up a studio for him in New Jersey. Through these various work experiences Buzzini expanded his knowledge and added to the precision of his technique.

From 1983 through 1986, Buzzini worked as a paperweight maker at Correia Art Glass in southern California. He was primarily designing and creating torchwork weights, although in the later years at Correia he began studying and experimenting with lampwork techniques on his own. In the fall of 1986 he set up his own studio in southern California. I Iere he can create the ty pe of detail and realism that his personal aesthetic demands.

5.81 Chris Buzzini at work

Says Buzzini, “Torchwork began to hold back my capabilities. It is a different kind of detail. Lampwork has allowed me to further my abilities to a more realistic approach. Because I studied and observed lampwork for years before I began it myself, it came together easily. Now the major components of my paperweights are my use of color, my attention to detail, and my sense of design.” Buzzini is producing superbly detailed lampwork weights that are botanically accurate and aesthetically satisfy ing.

In recognition of his talent, a Buzzini paperweight has been donated to the Wheaton Museum of Glass in Millville, New Jersey7; and one of his weights was used tor the cover of the Smithsonian Institution gift catalogue in the spring of 1988.

Chris Buzzini is the only artist to include a full name and date in a cane within the design. He also signs and dates his pieces in script on the side of each weight.

5.83 Chris Buzzini flonil bouquet

John Choko and Pete Lewis

A corporate designer at Wheaton Glass Works, John Choko first began experimenting with a torch in 1967.1 Iis goal was to create paperweights as members of his family had at Millville, more than fifty’ years before.

Choko was soon joined in his efforts by his friend and coworker, Pete Lewis. The two worked together purchasing new equipment, developing and refining paperweight techniques, and encouraging one another. After much experimentation they succeeded in creating pedestal rose weights. Choko is also known for his magnum-size salamander, snake, and flower weights. Lewis produced a number of miniature flowers.

Choko and Lewis paperweights are signed with a “JC” or “PL” cane respectively’. Date canes are also present in some of their pieces.

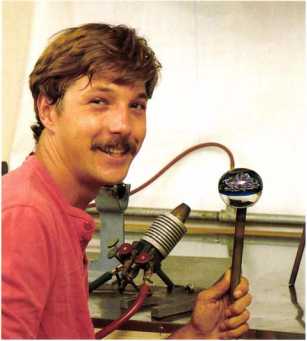

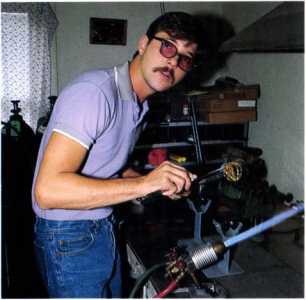

Randall Grubb

Randall Grubb came to glassmaking via an unusual route. Since childhood his great love has been building custom cars. I le built his first car at the age of thirteen and since then has designed and constructed dozens of automobiles. When he left home for business school at the University of Southern California, he was forced to leave his cars behind; it wasn’t long before he was desperate for a creative outlet.

Wandering into the glass studio in USC’s art department, he encountered for the first time the medium of hot glass. He fell in love with the hot glass process because its potential seemed unlimited. Grubb wrote his senior business plan on opening a hot glass studio. As part of his study he worked for a well-established studio in southern California. Such in-depth exposure to the many facets of hot glass gave tremendous experience to the young and talented Grubb; it also gave him his introduction to paperweights.

At first he worked with torchwork procedures, although they lacked the three-dimensional capability’ he wanted. When Grubb met Larry Selman at an antique show in southern California, he saw

5.85 Randall Grubb

5.87 Randall Grubb at work

lampwork weights for the first time. Thoroughly fascinated with them, he began experimenting with this technique.

At first he constructed the individual lampwork elements and included them in glass pieces he already knew how to make, such as perfume bottles. When he attained the equipment necessary to encase the elements in crystal he was already quite proficient at making lampwork motifs.

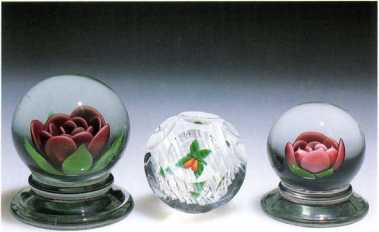

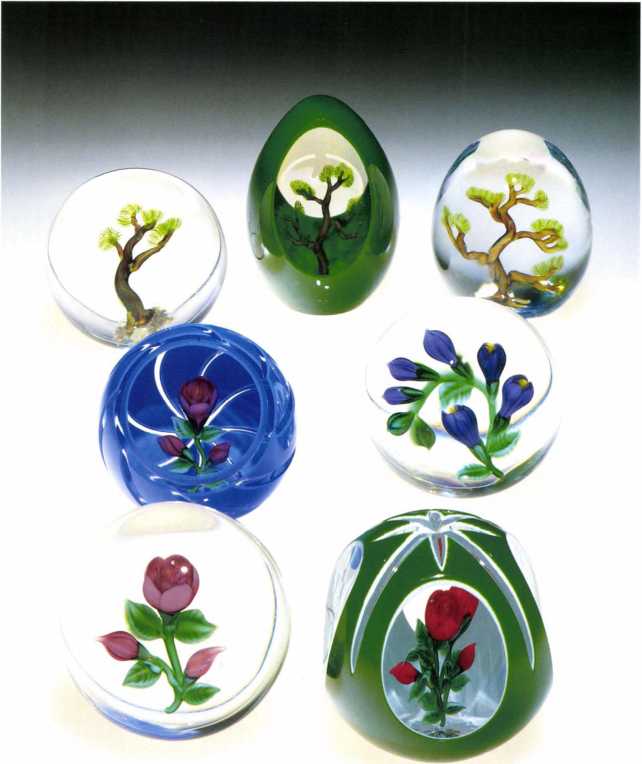

Although Grubb wrote his business plan on developing a large hot glass studio, he has been more interested in working as a studio artist. Currently he designs and creates his own line of lampwork paperweights. Grubb feels that outstanding color lends itself especially well to the lampwork process. Starting with the finest colored glass from Germany, he carefully combines two or three rods into one cane of just the rightshade. His weights include single-tiered flowers made up of a row of petals around vertical stamens, as well as two-tiered and multi-tiered flowers. His bud flowers and bud cluster are made up of a single mass of decorated glass. I le has also used the bonsai motif in his work, and he is one of the few American artists creating overlays.

Randall Grubb engraves his name and the date on the side of each weight.

Robert Hansen

A professional lampworker from Bridgeport, iYlichigan, Robert I lansen specializes in glass animals and figures. The brother of Ronald Hansen, he has also created some paperweights, most notably his lily-of-the-valley weight, which is fashioned after a famous piece by Clichy. Robert Hansen signs his w eights with a full signature in script on the base.

Ronald Hansen

As a boy growing up in Minnesota, Ronald Hansen came upon two hobo craftsmen—possibly immigrants from Europe—using a charcoal fire and improvised bellows to fashion glass ships out of soda bottles sawed in half. This was his introduction to glass.

Pursuing a career as a glass blower, he specialized in the manufacture of neon tubing. His interest in antique glass and the creative potential of the medium led him to paperweight making. Using only torches, he experimented with many different paperweight motifs, especially those popular in antique French weights.

Displaying snakes, fruits, and flowers, his successful weights are indeed collectible; unfortunately, weights flawed in production were not consistently destroyed. Finding their way into the hands of dealers or collectors, they have cast a shadow over his reputation. He is no longer making paperweights.

Ronald’s son, also named Robert, began making weights at the age of thirteen. By sixteen, he had weights displayed in the Museum at Wheaton Village in Millville. Especially noteworthy are his upright bouquets. Fie signs his weights with a striped blue and white “H” cane.

5.89 Charles Kaziun Charles Kaziun

A pioneer of modern paperweight making, Charles Kaziun has been working since 1939 to rediscover the lost techniques of the French glass factories of the last century. His work includes a wide range of millefiori, lampwork, and crimped flow er paperweights and related objects.

Kaziun s fascination with glass began when he was in grammar school and saw a glassblowing demonstration. When he was fourteen he saw a family of glassblowers, the Howells, demonstrating at the county fair in his home town of Brockton, Massachusetts. Each day he attended the fair and watched as the Howells demonstrated ornamental lampworking. Each evening he tried to duplicate what he had seen, heating broken pieces of glass from bike taillights, Bromo-Seltzer bottles, and cold cream jars over a crude Bunsen burner made out of a coffee can. Eventually the Howells refused to demonstrate w hen Kaziun was watching. But the determined young man got a job in the booth across the way so he could continue to observe them. Finally the Flowells hired him and gave him his first official training in glass work.

After graduation from high school Kaziun per- sued his interest in glass. He worked with neon tubing and scientific glassware. During World

War II he was involved in making top secret glass equipment. Each of his jobs further developed his skill and expertise in the shaping and manipulation of glass.

During these early years, an antique dealer asked Kaziun if he could copy an old glass paperweight-style button. Fascinated by the challenge, he began experimenting with the process. At the same time Kaziun met James D. Graham of the University of Pennsylvania, considered one of the finest scientific glassworkers in the country’. Impressed by Kaziun’s work, Graham hired him as his assistant in 1942, in the process teaching him even more about glass. Through Graham, Kaziun became familiar with some of the classic books, such as Evangeline Bergstrom’s Old Glass Paperweights, where for the first time he saw photographs of antique French paperweights.

Graham also introduced him to Emil Larson, one of the great American paperweight makers, who had worked at the glasshouses of Dorflinger and Mount Washington. At Larson’s home Kaziun saw his first Millville rose paperweight, and he was determined to create one on his ow n. After almost four years and several thousand dollars worth of experimentation, Kaziun perfected his version of the rose. Kaziun’s roses, which are smaller than their Millville counterparts, are today highly valued by collectors. Kaziun produced many crimped rose pedestal-style weights as well as developing other crimped flowers, including dogwood, daffodil, lily, crocus, and tulip. One of his most popular pieces is a miniature spider lily pedestal weight.

Over the years Kaziun has devoted himself to developing and refining his techniques. His work includes a wide range of paperweights and related objects of various styles and sizes, including several difficult-to-produce double and triple overlay pieces. He has also perfected a tine muslin and swirling latticinio for use as a ground in lampwork and millefiori weights.

Kaziun is one of the few contemporary paperweight artists in the world to develop millefiori weights that are on a par with antique pieces. He has produced spaced and patterned millefiori paperweights and a number of paperweight buttons. He frequently uses color grounds containing gold flecks. Kaziun also produced a series of weights containing the following silhouette canes:

Clover Rabbit Duck

1 lorse head Turtle Fisherman

Goose Heart Sunbonnet Sue

Whistler’s Mother

Over the years, Kaziun has used gold foil inclu

sions in many ot his paperweights and buttons. Some of his weights include a tiny gold bee.

Kaziun considers color a key factor in his work. He uses quality glass, some of which he collected from old French and Italian glass factories in the early years of his paperweight making. He also uses small amounts of glass from American factories, especiallvMount Washington and Dorflinger.

Kaziun s work has become extremely valuable and is consistently sought by collectors. At the 1983 Sotheby’s auction of paperweights from the Pauljokelson Collection, Charles Kaziun’s weights sold for prices ranging from Si,430 to $4,400. Jokelson, who appreciated Kaziun’s talent early in his glassmaking career, purchased weights from the artist for under Si00 in the 1950s.

Kaziun signs his weights with a 14k gold “K” and/or a millefiori “K” signature cane integrated into the design.

5.91 Paperweights and a perfume bottle by Charles Kazi inn

James Kontes and Nontas Kontes

The Kontes brothers, James and Nontas, began working with glass in 1939 at a small glass factor}’ in Vineland, New Jersey. In 1943 the two formed their own business, the Kontes Glass Company, which specialized in the production of laboratory and research glass.

In the early 1970s, they began to collect paperweights. Fascinated with both antique and modern weights, they turned a small section ot their factory into a paperweight studio. They produce their own crystal and make a wide variety of lampwork elements tor encasement. Some subjects are flowers, fruits, snakes, and composites.

Each brother works independently and marks his pieces with an individual cane. Nontas’s weights are marked with a bright yellow cane in clear crystal; James’s cane is black with a more elaborate red and yellow casing.

Dominick Labino

In 1963, after working for thirty-five years in the glass industry, Dominick Labino began blowing glass for the first time. He brought to his work in art glass the skills and experience he had gained in glass research and technology. Ilis free-form designs, swirled colors, and carefully planned air sculptures constituted a unique and inventive approach to paperweight making.

Born in Pennsylvania, Labino studied at die Carnegie Institute of Technology and the School of Design of the Toledo Museum of Art. After thirty-five years in the glass industry, he retired in 1965 as the Vice President and Director of Research and Development at Johns-Manville Fiber Glass, Inc. He also held sixty patents on glass compositions and processes.

Shortly before retiring Labino built a workshop in back of his home with the intention of continuing his research into glass production. After assisting in a seminar on glassblowing at the Toledo Museum of Art in 1962, Labino determined to study the production and control of color and form in art glass. He added to the equipment in his studio and in 1963 began blowing glass. He did original research into ancient glassmaking tech-

5.92 Dominick Labino marbrie weight

niques and wrote “The Egyptian Sand-Core Technique: A New Interpretation,” for the Journal of Glass Studies, Corning, New York, and Visual Ait in Glass, a history of the art.

Labino used no crimps or molds to form the motifs that make up his paperweights. Some of his designs include free-form flowers, upright tulips in a patented design with six or more petals crafted three-at-a-time, air enclosures, coiled snakes set on iridescent grounds, marbries, and abstract designs in clear or colored glass. Many of these motifs are surrounded by swirling veils of color achieved by adding silver to the melt.

Examples of Labino’s work are owned by more than twenty museums in the U.S. and Europe, including the Smithsonian Institution, The Corning Museum of Glass, and the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. To his credit are twenty-two one-man shows, including a retrospective at The Corning Museum in 1970. He also received several awards including the 1976 Glass Art Society Award for his contribution to the field of glass and to glass as a medium.

Labino, who died in 1987, influenced an entire generation of glass artists. His work as a paperweight maker marked a new direction in contemporary paperweight design.

Labino’s signature and the year are engraved on the base of each of his pieces.

Ken Rosenfeld

Born and raised in Los Angeles, paperweight artist Ken Rosenfeld specializes in detailed lampwork designs carried out in the traditional French style. His weights include a variety of flowers, floral bouquets, fruit, and vegetables.

Rosenfeld was a graduate student in ceramics at Southern Illinois University when he first encountered glass art. The fluid nature of this medium and the inherent rhythm involved in working with it attracted him strongly. Returning to Californiahe started a small glass studio with a partner. For a year the tw o artists sold their Tiffany-style pieces in street fairs. Then Rosenfeld worked at the studio of Steven Correia. During the next five years, he worked on their extensive production line, with time to develop some of his own ideas. Then he worked at Radnotti Glass Technology, a scientific glass house, becoming familiar with sophisticated glass technology and working with a much higher level of precision.

5.94 Ken Rosenfeld

Rosenfeld became interested in paperweight making after attending the 1980 PCA convention in New York City. He was greatly impressed by the exquisite collection of antique French paperweights on display; but it was the extraordinary work being done by contemporary artists that inspired him the most. He read everything he could find on the subject. He studied actual pieces anil talked to contemporary glass artists and collectors. When his first paperweights were offered for sale, the response was immediate and gratify ing.

Rosenfeld s work reflects his skills as a craftsman as well as his accomplishments as an artist and designer. Like most lampwork artists, he makes his own glass rods, so that his colors can be exact. Rosenfeld s colors are suble and sophisticated and give his weights a distinctive brilliance.Rosenfeld’s w eights are signed with an “R” cane and his name and the date are engraved on the base of each piece.

- 5.96 Gordon Smith

Gordon Smith

Gordon Smith’s first interest in glasswork was nurtured by his father, who had a precision machine shop in his basement. At the age of fourteen, his father gave him a melting torch and some scrap glass to experiment with. After high school Smith studied scientific glassblowing at Salem Community College. In 1978 he took his first job blowing scientific glass in Vineland, New Jersey.

Smith first became interested in paperweight making while working for Kontes Scientific Glass in Vineland. The owners of the company, James and Nontas Kontes, devoted much of their spare time to making paperweights. Smith became fascinated and inspired by their work. At that time he discovered Wheaton Village in nearby Millville. There he was able to study the work of Ray’ and Bob Banford and Paul Stankard. As he describes it, “That was all the inspiration that I needed. I felt like paperweight making was something I could do—and something I very’ much wanted to do.”

In 1981 Smith began to study, experiment, and ask questions. The Kontes brothers, the Banfords, and Paul Stankard all helped and encouraged the young artist, but there were certain aspects of paperweight making that he had to discover on his own. Within a y’ear Smith had broken through the technical harriers and was on his way to producing quality paperweights.

5.97 Bird of paradise by Gordon Smith

Smith now works in a small contemporary studio behind his home in Mays Landing, Newjersev. Working alone, he has created paperweights with well-formed lampwork floral motifs patterned alter orchids, irises, and other exotic flowers as well as a distinctive strawberry weight.

Smith signs his paperweights on the side with etched initials “GES” and the date.

Carolyn and Hugh Smith

Carolyn and Hugh Smith

Carolyn and I lugh Smith of Millville, Newjersev, began collecting weights in the late 1960s. Intrigued by the numerous design possibilities in his collection, Hugh began to study and experiment with glass. 1 le produced his first paperweight in 1969.

While assisting her husband in their new studio, Carolyn also became intrigued by the possibilities of weight production. By 1970 she had set up her own bench and began producing a variety of floral weights.

Smith paperweights are distinguished by subtle shadings in color and original, well-balanced designs. Each piece is signed with a color-coded millefiori initial cane of either “1 IS” or “CS.” The color denotes the year the weight was completed. An etched script signature is also found on the underside of some of their weights. Production ceased in the mid-1970s.

5.99 Paul Stankard

Paul Stankard

Paul Stankard, of Mantua, New Jersey, is perhaps the most prolific and accomplished paperweight artist working today. Says Stankard, “To some, the rigidity’ of glass and crystal may seem contrary to the delicacy of a flower. But 1 believe that, in trained hands, glass is the perfect substance for perpetuating its transient beauty. The technical and scientific knowledge I have acquired in my years as a glass artist permit me to take full advantage of this flexible and versatile medium.”

Completely self-taught, Stankard did not apprentice with any of the contemporary’ paperweight makers who worked in the glass-rich southern half of New Jersey. Ilis training was strictly industrial, and at the time he began his artistic efforts, he was manager of the scientific glassblowing department of a chemical and drug company.

5.101 Paul Stunkard cloistered botanical

With a growing interest in antique French paperweights, the Blaschka glass plants at the Peabody Museum of Harvard University’ inspired him to strive for botanical accuracy when he made his first paperweights in 1968.

Stankard’s early work featured superbly accurate lampwork flowers. Every detail of his pieces— the initial design, the exact coloration, the separate stages of construction—was carefully planned and executed. Stankard has a great interest in botany and knows the botanical terms for each part of the flower. He reinterprets what he sees through the strict rules of glassmaking chemistry and manipulation, capturing in glass the full range of his aesthetic experience. Many weights have intricate

root systems that are detailed with as much care and precision as the colorful blooms above ground.

1 hroughout his career Stankard has continued to expand the limits of the paperweight as an art form. I Ie produced many one-of-a-kind weights in search of the best design, color, and composition. And through continuous research and experimentation he has created several unique and innovative styles.

5.102 Paul Stankard cloistered botanical below the ground.

In 1982 Stankard developed his botanical series. These rectangular block-shaped sculptures break through the size and shape constraints of the traditional paperweight. Inside they reveal delicate, finely crafted flowers as well as the hidden beauties of the plant’s bulbs and root structures Many of the concepts S tankard developed in his botanical series are translated back into the traditional paperweight format in his environmental paperweights. In these pieces Stankard continues to explore under-earth imagery. Above the ground, in the dome of the weight, are colorful flowers and vegetation crafted in his meticulously realistic style. Hidden beneath the ground on the underside of the weight is a completely different world—an environment of earthy brown monotones and intricate root systems that take on human forms.

“I call these root structures ‘spirits under the earth’,” explains Stankard. “They’re not meant to be literal—they’re just impressions. For me, they represent the unseen energy’ and life beneath the

earth’s surface. I would wish that the personal response to my work need not depend on cultural background, nationality, or knowledge of glass. It should be an immediate, inward reaction. In the case of my paperweights, I hope it promotes a sense of well-being and sensitivity to nature’s beauty.”

Technically the environmentals are made up of two separate paperweights fused together. This approach, which Stankard first developed in his botanical series, creates a superb three-dimensionality’ within the weights.

Stankard’s spirits under the earth also appear in his cloistered botanical series. In these pieces colored glass is laminated on three sides of the block. “Suddenly the viewer’s eye is directed. The piece is no longer about glass; it’s about the flowers and roots suspended in their oxvn little environment,” explains Stankard.